When Brilliance Isn’t Enough:

The Commodore Amiga 500 Story

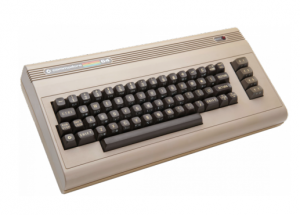

In 1987, Commodore released the Amiga 500, a home computer that immediately captured the imagination of gamers, hobbyists, and creative professionals alike. Despite its relatively affordable price, the Amiga 500 packed technological features far beyond what most competitors could offer at the time. It boasted a Motorola 68000 CPU running at 7.16 MHz, custom graphics and sound chips, and a multitasking operating system capable of running complex applications and games. Yet, despite these impressive specifications and the machine’s overwhelming capabilities, the Amiga 500 faced challenges that ultimately prevented it from dominating the market. Its story is a poignant example of how technological superiority does not always guarantee commercial success. The Amiga 500’s hardware was revolutionary for a home computer of its era. Its graphics chipset—comprising the Agnus, Denise, and Paula chips—enabled resolutions up to 640×512 in interlaced mode, 4096 colors with Hold-And-Modify (HAM) mode, and hardware sprites, which allowed for smooth animation and complex graphical effects. Meanwhile, its Paula sound chip delivered four-channel stereo audio, providing a level of sound sophistication that far outstripped the Commodore 64 and most IBM-compatible PCs of the mid-1980s. These capabilities made the Amiga 500 a favorite platform for game developers seeking to push the boundaries of home entertainment. Titles like Shadow of the Beast, Lotus Esprit Turbo Challenge, and The Secret of Monkey Island showcased the system’s stunning visuals and sound, leaving contemporaries struggling to match its performance.

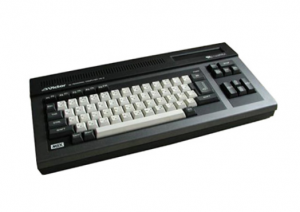

Yet the Amiga 500 was more than a gaming machine. Its operating system (OS) offered pre-emptive multitasking, a graphical user interface, and advanced file management, features far ahead of what PCs running DOS offered at the time. For creative professionals, the Amiga 500 enabled desktop publishing, animation, and music production at a fraction of the cost of professional workstations. Programs like Deluxe Paint and ProTracker became essential tools for artists and musicians, cementing the Amiga’s reputation as a platform for creativity. It was a computer that blurred the line between home entertainment and professional productivity, a rare feat in the late 1980s. Despite these advantages, the Amiga 500 faced stiff competition from multiple fronts. In the gaming market, the Commodore 64 still held strong due to its massive software library and entrenched user base. Meanwhile, the Atari ST series offered competitive graphics and sound, and its MIDI capabilities attracted musicians, especially in Europe. IBM PCs were becoming increasingly common in homes and offices, and Apple’s Macintosh continued to appeal to creative professionals with its software ecosystem and user-friendly interface. Unlike the Amiga, many of these competitors benefited from better marketing strategies, stronger corporate support, and wider software availability, factors that often mattered more to consumers than raw technical power.

Marketing missteps played a significant role in the Amiga 500’s commercial challenges. Commodore, while technically brilliant, struggled to communicate the computer’s capabilities to a mainstream audience. Consumers often did not understand the significance of pre-emptive multitasking, HAM graphics, or advanced sound channels, while competitors like Apple and IBM had clearer, more compelling messaging. Additionally, Commodore’s management frequently underinvested in software development support and failed to cultivate long-term relationships with third-party developers, which limited the system’s software ecosystem outside its core European markets. As a result, even though the Amiga 500 was technically superior, it did not always win against simpler, better-marketed, or more widely supported systems. Another challenge was the rapidly evolving market landscape. By the early 1990s, 16-bit consoles like the Sega Mega Drive and Super Nintendo Entertainment System began to dominate the gaming segment, offering ease of use and a consistent experience directly on the television. Meanwhile, PC clones were gaining software standardization, and Windows 3.0 and its successors made IBM-compatible machines more accessible for business and multimedia applications. The Amiga 500, despite its technical prowess, increasingly appeared as a niche system, struggling to maintain relevance as consumer expectations shifted and new competitors emerged.

Yet, the Amiga 500’s legacy has endured far beyond its commercial peak. Enthusiasts continue to celebrate its contributions to gaming, multimedia, and creative computing. Retro computing communities, emulators, and even modern re-releases have preserved the platform’s software and hardware innovations. Its architecture inspired generations of developers to explore complex graphics, audio programming, and multitasking in ways that were inaccessible on other home computers of the era. In Europe, particularly in Germany, the UK, and Scandinavia, the Amiga retains a cult following, with magazines, forums, and online archives devoted to its history, software, and hardware preservation. The Amiga 500 also helped define a broader cultural phenomenon. It demonstrated that technical excellence alone is insufficient in a competitive market; factors such as marketing, software availability, developer support, and timing often matter more than raw specifications. The Amiga’s story is a lesson in how innovation must be coupled with strategy, ecosystem development, and consumer communication. Commodore’s missteps with hardware successors and corporate management contributed to the eventual decline of the Amiga brand, yet the Amiga 500 itself remains a benchmark for what a home computer could achieve in the late 1980s.

Today, the Amiga 500 holds a unique place in computing history. Its hardware innovations set standards for graphics, sound, and multitasking that would influence later personal computers and gaming systems. The platform is celebrated in retro gaming circles, with emulators allowing modern users to experience its software library. Moreover, modern AmigaOS implementations continue to run on contemporary hardware, preserving the spirit of the system and demonstrating its lasting relevance. While Commodore as a company no longer exists, the Amiga 500 endures as a symbol of ingenuity, creativity, and the potential of home computing. In conclusion, the Commodore Amiga 500 exemplifies the paradox of technological superiority: a machine that, despite its advanced capabilities, could not fully dominate the market due to competition, marketing challenges, and shifting consumer landscapes. Nevertheless, its impact on gaming, multimedia, and creative computing remains profound. It inspired software developers, musicians, and artists, and its architectural innovations continue to be appreciated decades later. The Amiga 500 is a reminder that innovation, while necessary, is never sufficient without strategic support, and it stands as a lasting icon in the history of personal computing—a system where, although the best did not always win, its legacy remains undefeated.