Memotechin kotitietokone:

Se ei ole MSX, se on MTX!

1980-luvun alussa Britannia nousi yhdeksi maailman vilkkaimmista ja kilpailukykyisimmistä kotitietokonemarkkinoista. Vaatimattomasta ZX81:stä BBC Microon – henkilökohtaiset tietokoneet elivät kulta-aikaansa Yhdistyneessä kuningaskunnassa. Muutaman kuukauden välein kauppoihin ilmestyi uusi mikrotietokone, joka lupasi tuoda tulevaisuuden olohuoneisiin. Vuoteen 1984 mennessä markkinat olivat kuitenkin alkaneet rasittua oman painonsa alla. Kymmeniä pieniä yrityksiä tuli mukaan kilpailuun, mutta ne katosivat yhtä nopeasti, kun yleisön innostus laantui tai kun jättiläiset kuten Sinclair, Commodore ja Amstrad kiristivät otettaan. Tähän epävakaaseen maailmaan tuli yritys nimeltä Memotech Ltd. ja sen mukana yksi tyylikkäimmistä ja teknisesti hienostuneimmista brittiläisistä kotitietokoneista, mitä on koskaan rakennettu: Memotech MTX.

Memotech ei ollut alun perin tietokonevalmistaja. Geoff Boydin ja Robert Brantonin Oxfordshiressä perustama yritys saavutti varhaisen menestyksen tuottamalla korkealaatuisia RAM-laajennuksia Sinclair ZX81 -tietokoneelle, joka oli kuuluisa edullisuudestaan, mutta yhtä lailla tunnettu rajoituksistaan. Memotechin metallikoteloiset laajennukset saivat kiitosta luotettavuudestaan ja muotoilustaan, ja pian yritys päätti, että se voisi rakentaa kokonaisen tietokoneen samojen standardien mukaisesti. Tuloksena syntyi MTX-sarja – koneet, jotka erottuivat ammattimaisesta ulkonäöstään, vahvasta rakenteestaan ja aikansa edistyksellisistä ominaisuuksistaan.

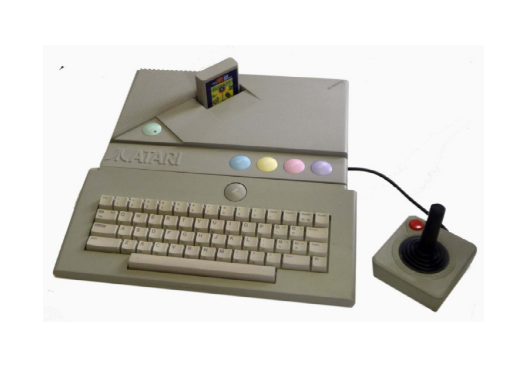

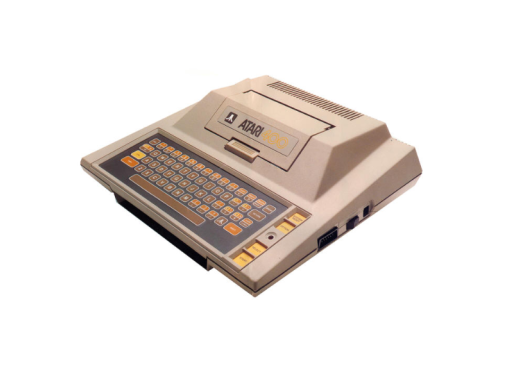

Ensimmäinen malli, MTX 500, ilmestyi vuoden 1983 puolivälissä, ja pian sen jälkeen tulivat MTX 512 ja myöhemmin RS128. Kaikissa malleissa oli sama tyylikäs musta harjattu alumiinikotelo, joka erottui selvästi useimpien kilpailijoiden muovikoteloista. Koneiden sisällä oli 4 MHz:n taajuudella toimiva Zilog Z80A -prosessori ja joko 32 tai 64 kt RAM-muistia. Niiden Texas Instruments -videopiiri pystyi näyttämään 256 × 192 pikselin grafiikkaa, kuusitoista väriä ja jopa kolmekymmentäkaksi laitteistospriittiä – ominaisuudet, jotka olivat verrattavissa samanaikaiseen ZX Spectrumiin ja haastoivat jopa uudemmat MSX-koneet. Ääni tuli SN76489A-piiriltä, joka tarjosi kolme ääntä ja kohinaa. Näppäimistö oli täysikokoinen, siinä oli kahdeksankymmentä näppäintä ja vankka mekaaninen toiminta, joka tuntui melkein ylelliseltä. Aikakaudella, jolloin kumiset näppäimet ja heiluvat näppäimet olivat yleisiä, MTX näytti ja tuntui vakavalta instrumentilta.

Teknisesti MTX oli monipuolinen. Sen laajennusportit mahdollistivat levyasemien, sarja- ja rinnakkaisliitäntöjen liittämisen ja jopa CP/M-käyttöjärjestelmän käytön ulkoisen FDX-moduulin kautta. Tämä tarkoitti, että WordStar- tai dBase-kaltaiset yritysohjelmistot voitiin periaatteessa käyttää kotikoneella. ROM-muistiin tallennettu sisäänrakennettu BASIC-tulkki oli tehokas ja sisälsi grafiikka- ja äänikomentoja, jotka tekivät koneesta ohjelmoijille ystävällisen. Memotech halusi selvästi tavoittaa sekä harrastajien että ammattilaisten markkinat – houkutella kotikäyttäjiä, jotka nauttivat peleistä ja ohjelmoinnista, mutta myös kouluja ja pienyrityksiä, jotka etsivät tehokasta mutta edullista CP/M-järjestelmää.

MTX tuli kuitenkin markkinoille vaarallisena aikana. Brittiläinen mikrotietokoneiden buumi oli alkamassa hiipua. Vuosina 1982 ja 1983 tietokoneita innokkaasti ostaneen yleisön asenne oli nyt varovaisempi, ja jälleenmyyjät olivat täynnä myymättömiä varastoja. Commodore oli laskenut hintoja VIC-20:llä ja myöhemmin hallitsevalla Commodore 64:llä, kun taas Amstrad valmistautui lanseeraamaan integroidun CPC 464:n aggressiivisella hinnalla. MTX, sen korkealaatuisella metallikotelolla ja täysikokoisella näppäimistöllä, oli väistämättä kalliimpi – noin 275 puntaa lanseeraushetkellä 32 KB:n mallille. Monille perheille se oli vaikea päätös, kun markkinoilla oli halvempia ja paremmin tuettuja vaihtoehtoja.

Ohjelmistotuki osoittautui ratkaisevaksi heikkoudeksi. Teknisistä vahvuuksistaan huolimatta MTX:llä ei ollut vahvaa pelien tai oppimateriaalien valikoimaa, ja kehittäjät olivat haluttomia sitoutumaan uuteen alustaan. Memotech toivoi, että yhteensopivuus kehittyvän MSX-standardin kanssa voisi auttaa, mutta MTX poikkesi lopulta juuri tarpeeksi, jotta ohjelmistojen suora jakaminen oli mahdotonta. Ilman kykyä ajaa Spectrum- tai Commodore-ohjelmia ja ilman MSX-merkkiä se jäi hankalaan välitilaan standardien välillä. Muutama hyvä nimike ilmestyi –Attack of the Mutant Camels, Kilopede, sekä Flight Simulator among them—but they were not enough to establish a thriving ecosystem.

Silti niille harvoille käyttäjille, jotka ostivat MTX:n, se oli ilo. Ohjelmoijat arvostivat koneen nopeaa BASIC-kieltä ja mahdollisuutta kirjoittaa assembler-kielellä sisäänrakennetun monitorin avulla. Grafiikka- ja äänisirut tarjosivat luovia mahdollisuuksia, ja vankka näppäimistö teki kirjoittamisesta miellyttävää. Valinnainen FDX-järjestelmä, jossa oli kaksi levykeasemaa ja CP/M-yhteensopivuus, teki MTX:stä luotettavan pienyritystietokoneen. Koulutusympäristöissä se tarjosi kestävyyttä ja laajennettavuutta. Harrastajien keskuudessa vallitsi käsitys, että MTX oli kone niille, jotka arvostivat laatua enemmän kuin muotia – todellisten tuntijoiden valinta.

Valitettavasti laatu yksinään ei riittänyt pelastamaan yritystä. Memotech investoi voimakkaasti tuotantolaitoksiin odottaen suuria myyntimääriä, jotka eivät koskaan toteutuneet. Yritys pyrki myös kunnianhimoisiin vientisopimuksiin, mukaan lukien ehdotettu sopimus tietokoneiden toimittamisesta Neuvostoliiton kouluihin, mutta kylmän sodan poliittiset ja logistiset monimutkaisuudet vesittivät suunnitelman. Vuoteen 1985 mennessä myymättömät varastot kasvoivat, ja yritys joutui laskemaan hintoja rajusti: MTX 500:n hinta laski joissakin loppuunmyynneissä alle 80 puntaan. Pian sen jälkeen Memotech joutui selvitystilaan. MTX-sarjan tuotanto lopetettiin, ja jäljellä olevat varastot katosivat vähitellen markkinoilta.

Jälkikäteen tarkasteltuna Memotech MTX:n epäonnistuminen ei johtunut huonosta suunnittelusta, vaan ajoituksesta ja markkinatilanteesta. Vuoteen 1984 mennessä kuluttajat olivat yhä enemmän kiinnostuneita hinnasta ja ohjelmistokirjastoista kuin laitteiston tyylikkyydestä. ZX Spectrum hallitsi kotipelimarkkinoita pelkän volyymin ja kehittäjien tuen ansiosta. BBC Micro oli valloittanut koulut. Commodore ja Amstrad kilpailivat valtavirrassa, jättäen vain vähän tilaa tyylikkäälle ulkopuoliselle yrittäjälle. Yritysten tietotekniikassa CP/M-markkinarako oli nopeasti korvautumassa IBM-yhteensopivilla tietokoneilla. MTX oli kone, joka oli jäänyt kahden maailman väliin: liian hienostunut ja kallis satunnaiselle käyttäjälle, liian pieni ja yhteensopimaton yritysmaailmalle.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Kaupallisesta pettymyksestä huolimatta MTX jätti jälkensä tietokonekulttuuriin. Keräilijät ihailevat yhä sen ammattitaitoista valmistusta, näppäimistön sujuvuutta ja alumiinikuoren hillittyä kauneutta. Monin tavoin se symboloi brittiläisen mikrotietokoneiden aikakauden parhaita puolia: insinöörien kunnianhimoa, innovaatiohalua ja uskoa siihen, että henkilökohtaiset tietokoneet voivat olla sekä tyylikkäitä että helposti saatavilla. Vaikka MTX:ää myytiin vain muutamia kymmeniä tuhansia kappaleita, se on edelleen suosikki retrotietokoneiden harrastajien keskuudessa, jotka näkevät siinä toteuttamattoman idean – ajatuksen, että brittiläinen kone voisi kilpailla laadulla, ei vain hinnalla.

Memotechin ja sen MTX-tietokoneiden tarina on lopulta sekä inspiroiva että traaginen. Se osoittaa, kuinka lahjakkuus ja visio voivat tuottaa merkittävää teknologiaa, mutta myös kuinka armoton markkinat voivat olla. MTX seisoi ylpeänä vuoden 1984 kotitietokoneiden joukossa, sen metalli kiilsi muiden hauras muovin keskellä, mutta kun pöly laskeutui, massamarkkinoille suunnatut koneet olivat selvinneet. Memotech katosi vuonna 1985, jättäen jälkeensä vain muiston kauniisti rakennetusta koneesta, joka saapui hieman liian myöhään ja maksoi hieman liikaa.

Kun nykyään käynnistää säilyneen MTX-tietokoneen ja näkee sen puhtaan sinisen näytön välähtävän eloon, on helppo kuvitella, mitä olisi voinut olla. Aikana, jolloin tietotekniikka oli vielä seikkailu, Memotech MTX edusti sekä täydellisyyden unelmaa että markkinoiden todellisuutta. Se muistuttaa siitä, että teknologian historiaa eivät kirjoita vain voittajat, vaan myös tyylikkäät, tuhoon tuomitut koneet, jotka uskalsivat kilpailla erilaisuudellaan ja poiketa massasta.