The home computer from Memotech:

It’s not MSX. It is MTX!

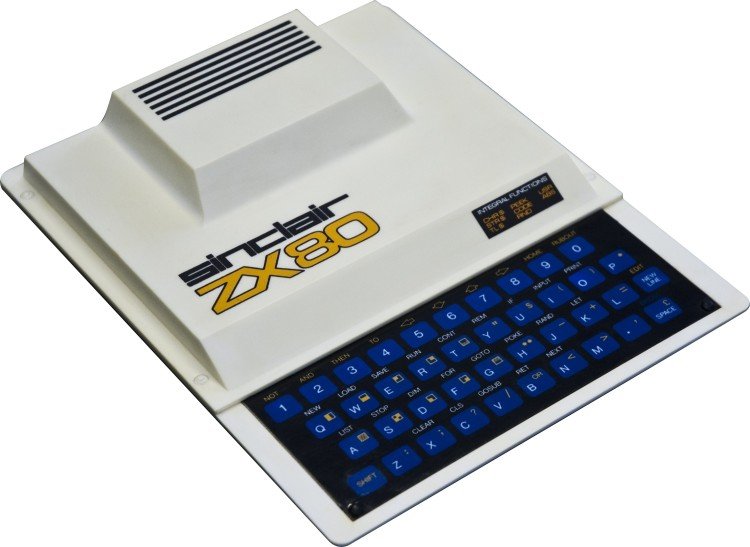

In the early 1980s, Britain became one of the most vibrant and competitive home-computer markets in the world. From the modest ZX81 to the BBC Micro, personal computing in the United Kingdom was experiencing a golden age. Every few months, a new micro appeared on the shelves, promising to bring the future into the living room. Yet by 1984, that market was also beginning to strain under its own weight. Dozens of small companies entered the race, and just as quickly vanished when the public’s enthusiasm cooled or when giants such as Sinclair, Commodore, and Amstrad tightened their grip. Into this volatile world came a company called Memotech Ltd., and with it, one of the most stylish and technically refined British home computers ever built: the Memotech MTX.

Memotech was not originally a computer manufacturer. Founded by Geoff Boyd and Robert Branton in Oxfordshire, the company gained early success producing high-quality RAM expansions for the Sinclair ZX81, a machine famous for its affordability but equally notorious for its limitations. Memotech’s metal-cased expansions were praised for their reliability and design, and soon the firm decided that it could build an entire computer to the same standard. What emerged was the MTX series—machines that would stand out for their professional appearance, strong build quality, and advanced specification for the time.

The first model, the MTX 500, appeared in mid-1983, followed soon by the MTX 512 and later the RS128. All shared the same elegant black brushed-aluminum case, a far cry from the plastic shells of most of their rivals. Inside, the machines ran on a Zilog Z80A processor clocked at 4 MHz, with either 32 KB or 64 KB of RAM. Their Texas Instruments video chip could display 256 × 192 graphics, sixteen colours, and up to thirty-two hardware sprites—capabilities that compared favourably to the contemporaneous ZX Spectrum and even challenged the newer MSX machines. Sound came from the SN76489A chip, offering three tones and noise. The keyboard was full-sized, with eighty keys and a solid mechanical action that felt almost luxurious. In an era when rubber chiclets and wobbly keys were common, the MTX looked and felt like a serious instrument.

Technically, the MTX was versatile. Its expansion ports allowed the attachment of disk drives, serial and parallel interfaces, and even the running of the CP/M operating system through an external module called the FDX. That meant business software such as WordStar or dBase could, in principle, run on a home machine. The built-in BASIC interpreter, stored in ROM, was powerful and included commands for graphics and sound that made the machine friendly to programmers. Memotech clearly wanted to straddle both the hobbyist and professional markets—appealing to the home user who enjoyed games and coding, but also to schools and small businesses seeking a capable yet affordable CP/M system.

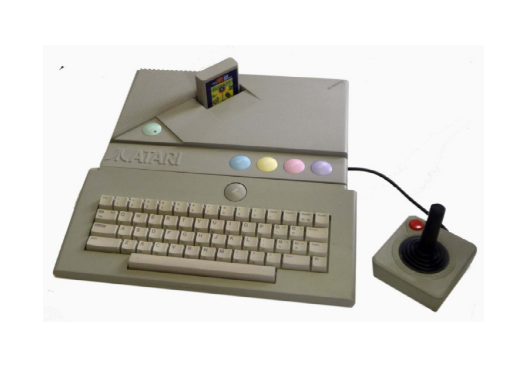

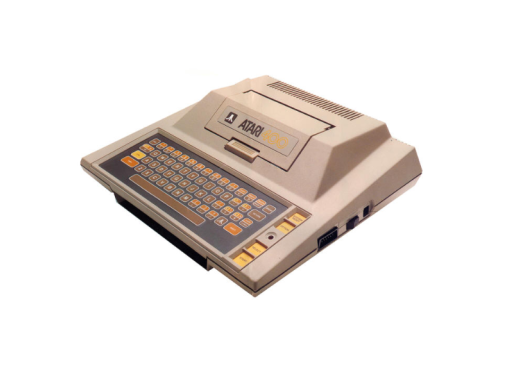

Yet the MTX entered the market at a perilous time. The British micro boom was beginning to falter. The public that had enthusiastically bought computers in 1982 and 1983 was now more cautious, and retailers were flooded with unsold stock. Commodore had driven prices down with the VIC-20 and later the dominant Commodore 64, while Amstrad was preparing to launch its integrated CPC 464 at an aggressive price. The MTX, with its premium metal case and full-sized keyboard, inevitably cost more—around £275 at launch for the 32 KB model. For many families, that was a difficult proposition when cheaper and better-supported alternatives existed.

Software support proved to be the decisive weakness. Despite its technical strengths, the MTX arrived without a strong base of games or educational titles, and developers were reluctant to commit to another new platform. Memotech hoped that compatibility with the emerging MSX standard might help, but the MTX ultimately differed just enough to make direct software sharing impossible. Without the ability to run Spectrum or Commodore programs, and lacking an MSX badge, it occupied an awkward no-man’s-land between standards. A few good titles appeared—Attack of the Mutant Camels, Kilopede, and Flight Simulator among them—but they were not enough to establish a thriving ecosystem.

Still, for the small number of users who did buy one, the MTX was a delight. Programmers appreciated the machine’s fast BASIC and the ability to write in assembler using the built-in monitor. The graphics and sound chips offered creative potential, and the solid keyboard made it a pleasure to type on. The optional FDX system, with its twin floppy drives and CP/M compatibility, turned the MTX into a credible small-business computer. In educational settings, it offered durability and expandability. There was a sense among enthusiasts that the MTX was a machine for those who cared about quality rather than fashion—a connoisseur’s choice.

Unfortunately, quality alone could not save it. Memotech invested heavily in production facilities, expecting large sales volumes that never materialized. The company also pursued ambitious export deals, including a proposed contract to supply computers to Soviet schools, but the political and logistical complexities of the Cold War scuttled the plan. By 1985, unsold stock piled up, and the firm was forced to slash prices drastically: the MTX 500 fell to under £80 in some clearance sales. Not long afterward, Memotech went into receivership. Production of the MTX line ceased, and the remaining inventory gradually disappeared from the market.

In hindsight, the Memotech MTX’s failure was not due to poor engineering but to timing and market realities. By 1984, consumers were increasingly driven by price and software libraries rather than by hardware elegance. The ZX Spectrum dominated the home-gaming market through sheer volume and developer support. The BBC Micro had captured the education sector. Commodore and Amstrad were fighting over the mainstream, leaving little room for a stylish outsider. Even in business computing, the CP/M niche was rapidly being replaced by IBM-compatible PCs. The MTX was a machine caught between worlds: too refined and expensive for the casual user, too small and incompatible for the business world.

Yet for all its commercial disappointment, the MTX left a mark on computing culture. Collectors today still admire its craftsmanship, the smoothness of its keyboard, and the understated beauty of its aluminum shell. In many ways, it symbolized what was best about the British microcomputer era: a spirit of engineering ambition, a willingness to innovate, and a belief that personal computing could be elegant as well as accessible. Though only a few tens of thousands were ever sold, the MTX remains a favourite among retro-computer enthusiasts who see in it the road not taken—the idea that a British machine could compete on quality, not just price.

The story of Memotech and its MTX computers is, in the end, both inspiring and tragic. It demonstrates how talent and vision can produce remarkable technology, yet also how unforgiving the marketplace can be. The MTX stood proudly among the crowded ranks of 1984’s home computers, its metal gleaming where others offered brittle plastic, but when the dust settled, it was the mass-market machines that survived. Memotech disappeared by 1985, leaving behind only the memory of a beautifully built machine that arrived just a little too late and cost just a little too much.

Today, when one powers up a surviving MTX and sees its clean blue screen flicker to life, it is easy to imagine what might have been. In a time when computing was still an adventure, the Memotech MTX represented both the dream of perfection and the reality of the marketplace. It is a reminder that technology’s history is written not only by the winners, but also by the elegant, doomed machines that dared to compete.