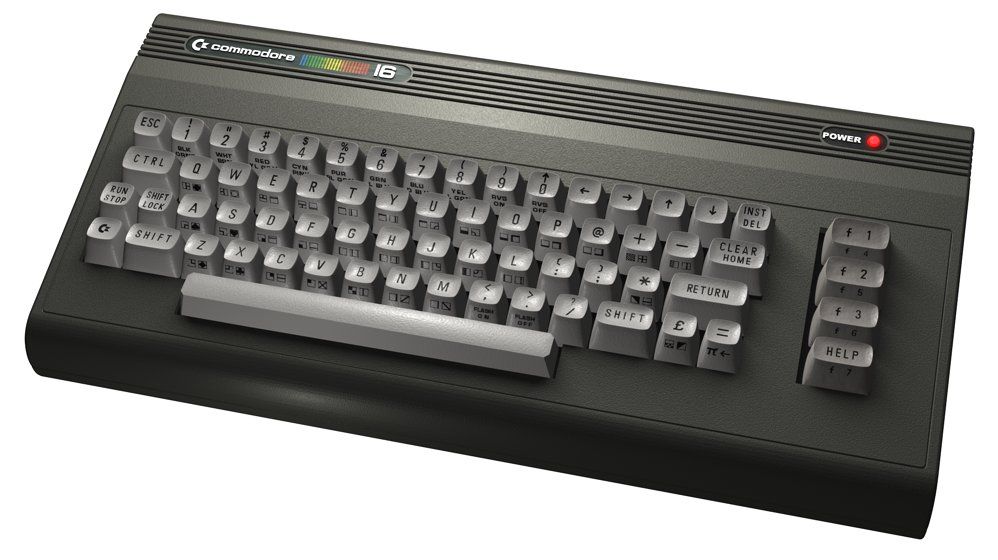

Commodore 16 – Tramiels Exit Device

The story of the Commodore 16 and the TED (Text Editing Device) series is a curious chapter in the history of home computing. Launched in 1984, the Commodore 16 was part of a new line of low-cost home computers designed to replace the aging VIC-20 and to capture markets where affordability was paramount. Although it never achieved the same commercial success as the Commodore 64, it remains notable for its role in shaping computer use in certain regions, particularly Eastern Europe, and for reflecting the broader strategies and anxieties of the computer industry during the mid-1980s. The Commodore 16 was released in June 1984, alongside its siblings, the Commodore Plus/4 and Commodore 116. Collectively, these machines were known as the “TED series” because they were built around the TED chip, which handled both graphics and sound as well as DRAM refresh and I/O functions. The TED was intended to simplify hardware design, reduce costs, and make the machines more affordable than the more powerful Commodore 64.

The launch of the TED series coincided with significant internal changes at Commodore. Jack Tramiel, the company’s hard-driving CEO who had overseen the success of the VIC-20 and Commodore 64, left in January 1984 after a conflict with the board. Nevertheless, the TED machines had been in development under his direction, and they reflected his philosophy of low-cost, mass-market computing. Tramiel’s famous remark—“The Japanese are coming”—referred to his fear that Japanese companies like Sony and Matsushita would soon flood Western markets with inexpensive home computers, much as they had previously done with calculators and televisions. The TED series was intended as a preemptive strike, offering stripped-down but affordable machines that could compete on price while maintaining compatibility with Commodore’s distribution channels.

Technical Characteristics

The Commodore 16 featured 16 KB of RAM (hence the name) and the TED chip, which could display up to 121 colors—an impressive number for its time—though it was limited to relatively low-resolution graphics modes. Sound capabilities were modest, with only two channels and limited features compared to the iconic SID chip in the Commodore 64. The keyboard layout resembled that of the VIC-20 and C64 but with some changes that confused early users.The Plus/4, the higher-end member of the TED family, shipped with 64 KB of RAM and built-in productivity software, including a word processor, spreadsheet, database, and graphing package. However, these applications were primitive compared to commercial alternatives and failed to impress most reviewers.

Despite being positioned partly as a productivity machine, the Commodore 16 and its relatives developed a vibrant gaming library, particularly in Europe. Because the machine was not directly compatible with the Commodore 64, developers had to produce titles specifically for the TED series. This limited the number of high-profile releases but encouraged smaller studios and local developers to create content. Publishers such as Mastertronic, Kingsoft, Anirog, and Commodore itself played leading roles in supplying software for the TED series. Mastertronic, with its budget-priced titles, was especially important, as the low-cost games matched the affordability of the hardware.

While the Commodore 16 was never a major success in the United States, it found significant popularity in Europe, particularly in Eastern Bloc countries such as Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. There, the affordability of the C16 and Plus/4 made them attractive alternatives to more expensive Western systems. Furthermore, local developers embraced the platform, producing a large number of games and utilities that sustained the user community well into the 1990s. In Hungary, for instance, companies like Novotrade (later Appaloosa Interactive) created software for the TED machines, while a thriving demoscene emerged that pushed the hardware to its limits. The C16 became an accessible entry point for young programmers behind the Iron Curtain, where access to Western computers was often limited. In terms of sales, the Commodore 16 and its TED siblings never matched the runaway success of the Commodore 64. Estimates suggest that the Commodore 16 sold around 1 million units worldwide, with the broader TED family reaching perhaps 2 million. By contrast, the Commodore 64 sold over 17 million units. The relatively low sales figures were due to the lack of compatibility with the C64 software library, the weak bundled productivity software on the Plus/4, and confusion in the marketplace about the purpose of the new machines.

Reception in the Press

The contemporary press was lukewarm, if not outright critical, toward the Commodore 16 and TED series. Many reviewers compared the C16 unfavorably with the Commodore 64, which was still on the market and only modestly more expensive yet offered far superior graphics and sound. Publications in North America often questioned why anyone would buy a C16 when the C64 existed. European magazines, however, were somewhat kinder, noting that the C16 filled a niche as a low-cost computer for beginners. Still, the machine was widely perceived as a step backward in capability, and the Plus/4’s bundled software was described as inadequate for serious business use. Overall, the TED series suffered from a confused identity: not powerful enough for professionals, not compatible enough for gamers, and not distinctive enough to stand out in a crowded market.

The Legacy of “The Japanese Are Coming”

Jack Tramiel’s warning about Japanese competition helps explain why the TED series came to exist. In the early 1980s, Japanese companies were indeed experimenting with inexpensive home computers, and there was widespread fear in the U.S. and Europe that they would dominate the market as they had with consumer electronics. Tramiel believed that Commodore’s survival depended on delivering machines at prices so low that competitors could not match them. The C16 and its siblings were meant to be disposable, mass-market computers that could undercut rivals. Ironically, Tramiel left Commodore before the TED machines were released, and he went on to acquire Atari’s consumer division, launching the Atari ST line instead. Without his leadership, Commodore mismanaged the TED rollout, failing to position the machines clearly in relation to the VIC-20, C64, and business markets. In retrospect, Tramiel’s instincts about competition were correct, but the execution of the TED strategy was flawed.

The Commodore 16 and the TED series occupy a peculiar place in the history of personal computing. Launched in 1984 as part of a defensive strategy against anticipated Japanese competition, they were technologically interesting but commercially underwhelming. Their incompatibility with the C64 library, limited sound capabilities, and poorly conceived productivity software undermined their appeal in most Western markets. Nevertheless, the Commodore 16 found an unexpected second life in Eastern Europe, where its affordability and accessibility made it a popular entry-level computer. Local developers, hobbyists, and demoscene enthusiasts extended its relevance far beyond what sales figures alone would suggest. While the TED series never lived up to its potential as a global platform, it remains a reminder of the volatile and experimental nature of the 1980s computer industry—and of the tensions between affordability, compatibility, and capability in a rapidly evolving marketplace.