An Educational Computer of the Early 1980s

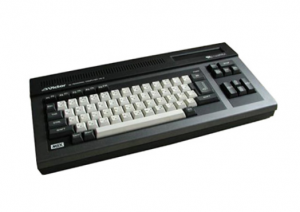

The early 1980s were marked by a rapid proliferation of home and educational computers, with dozens of manufacturers seeking a foothold in the emerging personal computer market. Among the more unusual systems of this era was the Microprofessor MPF-II, a small and relatively obscure machine produced by the Taiwanese company Multitech (which would later rename itself Acer). The MPF-II was released in 1982, at a time when the Apple II, Commodore VIC-20, and Sinclair ZX Spectrum were dominating the attention of hobbyists and consumers in different parts of the world. Rather than aiming directly at the mainstream home computer market, the MPF-II was designed primarily as an educational and training computer, intended to introduce beginners to the fundamentals of programming and microprocessor logic. The Microprofessor MPF-II was built around the MOS Technology 6502 microprocessor, the same CPU family that powered the Apple II, Commodore 64, and Atari 8-bit systems. However, unlike those machines, the MPF-II had a more limited architecture and was packaged as a compact learning tool rather than a full-fledged multimedia system. Its operating environment revolved around a built-in BASIC interpreter, giving learners immediate access to programming capabilities.

One of the MPF-II’s distinguishing features was its ROM-based software set. While it came with a limited built-in BASIC, users could expand its functionality through plug-in ROM cartridges that offered utilities, educational programs, or games. This modularity reflected its educational mission: schools and training institutes could tailor the system for different uses without needing expensive peripherals. Another unusual aspect was its low-cost, compact design. The MPF-II was often sold bundled with manuals that emphasized programming exercises, making it a hybrid between a training kit and a home computer. Visually, the MPF-II lacked the sleek casing of better-known home micros. It had a minimal keyboard, limited graphics capabilities, and modest sound support. Its display output was generally text-oriented, although simple graphics and colors were possible. These constraints made it less attractive as a mainstream gaming machine, but well suited for instructional settings. Despite its limitations, the MPF-II did have a modest library of games and educational titles. Because the system was compatible to some extent with Apple II software, certain programs were adapted or ported, though not always perfectly. Among the better-known titles available on the MPF-II were simplified versions of classic arcade-style games such as Breakout, Pac-Man clones, and Space Invaders variants. These were often distributed not by major Western publishers but by Asian educational software companies or local distributors bundling cartridges with the machine. Educational software was perhaps more central to its identity. Programs teaching mathematics, simple physics, and typing were common. The company itself, Multitech, published a series of cartridges designed to reinforce the MPF-II’s role as a classroom computer. Because the platform never developed a large independent developer community, most of its games and utilities came directly from the manufacturer or affiliated partners.

The MPF-II found its strongest markets in Asia and parts of Europe, particularly in regions where educational authorities or vocational schools were seeking inexpensive training computers. In countries like Taiwan and parts of Eastern Europe, the system gained a modest foothold because of its affordability and focus on programming education. In Western Europe, particularly the UK and Germany, the MPF-II was marketed but never achieved mainstream popularity, as machines like the ZX Spectrum, Commodore 64, and Amstrad CPC offered far richer gaming and home applications at similar prices. In the United States, the MPF-II was virtually invisible due to the dominance of Apple, Atari, and Commodore. Exact sales figures are difficult to determine, but historians generally agree that the MPF-II sold in the tens of thousands of units worldwide, not in the millions like its better-known contemporaries. Its limited appeal as a home entertainment device kept its market share small, but as a training computer, it met its niche goals reasonably well.

To better understand the place of the MPF-II in computing history, it is useful to compare it with some of its major contemporaries. The Commodore VIC-20 (1980) was marketed as the “friendly computer” and became the first computer to sell more than one million units. It offered color graphics, sound, and a large library of games at a very low price. For a family looking for both educational and entertainment value, the VIC-20 was far more appealing than the MPF-II. The Sinclair ZX Spectrum (1982), released in the same year as the MPF-II, took Europe by storm with its compact design, color display, and affordable price point. While the Spectrum also had limited hardware compared to higher-end machines, it inspired a massive software scene, especially in the United Kingdom. Thousands of games were released, creating a thriving ecosystem that the MPF-II never achieved.

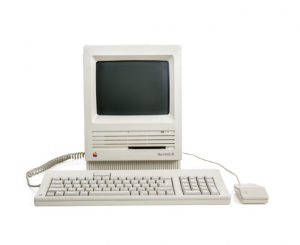

By contrast, the Apple II (1977) was a fully realized personal computer platform, with expandability, robust graphics modes, and an extensive software library. Although far more expensive than the MPF-II, the Apple II established itself as a mainstay in education, small business, and even gaming. The MPF-II, which borrowed elements from the Apple II architecture but stripped them down, was perceived by many reviewers as an “Apple II imitation” that lacked the compatibility to benefit from Apple’s ecosystem. Even the Commodore 64 (1982), launched the same year, highlighted the MPF-II’s shortcomings. The C64’s advanced graphics and sound hardware, coupled with aggressive pricing and Commodore’s global distribution, made it the best-selling computer of the 1980s. Compared to the C64, the MPF-II felt more like a stopgap teaching tool than a platform for creativity, entertainment, or serious productivity. This contrast explains much of the MPF-II’s limited commercial impact. While it succeeded in fulfilling its narrow mission as an educational trainer, it could not compete in the broader consumer marketplace, where multimedia features, gaming libraries, and strong distribution networks determined success.

Contemporary press coverage of the MPF-II was mixed. Educational and technical journals often praised it for being inexpensive and relatively easy to use as an introduction to microcomputing. Reviewers highlighted its usefulness in teaching BASIC and familiarizing students with microprocessor concepts. Its bundled manuals were considered clear and accessible, which made the machine attractive for schools with limited budgets. However, mainstream computer magazines often criticized the MPF-II for its weak performance compared to similarly priced competitors. The limited keyboard, poor sound, and modest graphics capabilities meant that it could not compete with the wave of gaming-oriented micros flooding the consumer market. Some reviewers regarded it as a “cut-down Apple II” that lacked the compatibility and polish necessary to succeed outside classrooms. As such, while it earned respect as an educational trainer, it was rarely recommended for general home computing. The Microprofessor MPF-II ultimately occupies a minor place in the history of personal computing. Its importance lies less in its technical achievements than in its role as part of the early career of Multitech/Acer, which would go on to become a major global PC manufacturer. The MPF-II represents a moment when many companies experimented with producing training computers to satisfy the growing demand for computer literacy in the early 1980s. While overshadowed by giants like the Commodore 64 and Sinclair Spectrum, the MPF-II contributed to spreading programming knowledge, especially in regions where more powerful systems were either too costly or unavailable. Released in 1982, the Microprofessor MPF-II was an unusual educational computer that sought to bridge the gap between training kits and home micros. With its limited but serviceable BASIC environment, cartridge-based expandability, and focus on classroom use, it carved out a small niche in Asia and Europe. Its software library was modest, with educational programs and simple arcade-style titles published mainly by Multitech and affiliated partners. Though it sold only in modest numbers and was often criticized by the press for its limited multimedia features, the MPF-II remains a significant artifact of the early 1980s computing boom, and a stepping stone in the evolution of Acer as a global technology company.

A few games were also released, such as:

Autobahn

Beetle

Eliminator

Galaxy Travel

Gobbler

Gorgon

Head On

Micro Chess

Obstacle

Star Blazer

War!

Worms Wall