The MSX standard was designed by ASCII Corporation in collaboration with Microsoft, which supplied the computers’ basic interpreter, “MicroSoft eXtended BASIC.” This partly explains the abbreviation in the computers’ MSX name. Kazuhiko Nishi of Japan is widely recognized as the father of the MSX concept.

The name “MSX” can mean much more than MicroSoft eXtended. Nishi said he used the abbreviation MSX to refer to the Matsushita Sony X-machine, where X could refer to the company with which Nishi was negotiating the production of the devices. Nishi initially wanted to name the standard either “NSX” (Nishi Sony X) or “MNX” (Matsushita Nishi X), but Honda had already taken the name “NSX.” Following this logic, Nishi could also say that MS refers to MicroSoft. According to Nishi, Matsushita and Sony were the most important companies manufacturing MSX machines. In 1976, Kazuhiko Nishi was studying at the prestigious Waseda University in Tokyo. He was already fascinated by the new world of computers, software, and electronics. Together with his friends, he set out to create a game that would run on the General Instrument AY-3-8500 processor. These were the same processors used in the Odyssey 300 console and Coleco Telstar.

Nishi wanted to build the console himself, so he visited General Instrument to buy some chips, but was told that the chips were not available for retail purchase. Since he didn’t have enough money to buy large quantities of chips, he decided to abandon the idea. In August 1977, Kazuhiko Nishi picked up the phone and called Microsoft headquarters. Bill Gates answered the call, and at the end of the conversation, Nishi offered Bill Gates a plane ticket to Tokyo so they could meet in person. Gates declined the offer because he was too busy to travel, so instead, Nishi flew to the US to meet Bill Gates. Nishi and Gates finally met in person two months later at a computer exhibition. Nishi and Gates talked for over nine hours and realized they had a lot in common. Both men were 21 years old, came from similar social backgrounds, had both left college to start their companies, and shared the same passion for computing and were certain that the software and computer markets were about to explode. Their personalities complemented each other well. Nishi was friendly, persuasive, and had all the skills you would expect from a professional businessman, while Gates had a more theoretical approach to things. Nishi became Microsoft’s vice president, and his company, ASCII, became Microsoft’s official representative in Japan. Nishi’s relationship with Bill Gates helped ASCII Corporation grow. Microsoft and ASCII Corporation jointly developed MSX, a new personal computer standard for the market.

Kazuhiko Nishi called Kazuya Watanabe, president of NEC Corp., and convinced him to come to the United States to meet Bill Gates and Paul Allen, the founders of Microsoft. The meeting with the young owners of Microsoft was decisive. Watanabe was impressed by these young men. He returned to Tokyo with a project in mind, which he presented to his company’s board: to build a new computer with the support of Microsoft and ASCII. In 1979, the result of this project was completed, and the new “NEC PC 8000” computer was born, which was the first Japanese home computer. It was also the first home computer with Microsoft’s built-in Basic language. The NEC PC 8000 was a commercial success and a great opportunity for Microsoft and ASCII. Nish’s company ASCII had a large share of the software market in Japan, largely due to its collaboration with Microsoft. It was already a good situation, but it was clear to Nish that the home computer market needed a standard. For example, Matsushita, which was the world’s largest electronics company at the time, demanded standardization in the industry.

While Spectravideo was building and marketing it

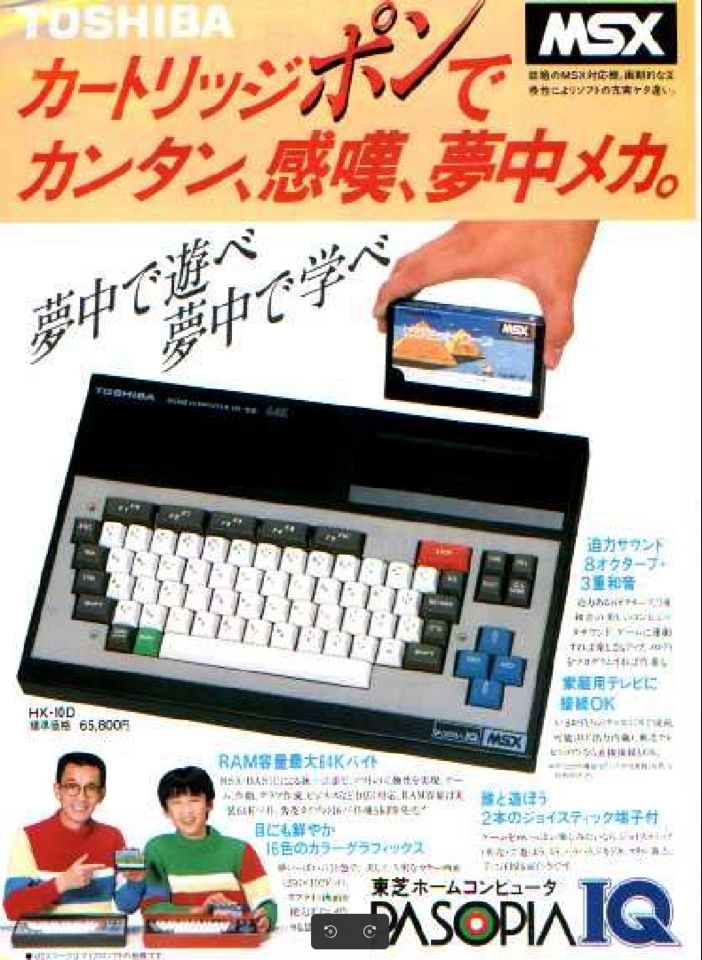

s SVI series home computer, Kazuhiko visited leading Japanese electronics companies. He brought along a Spectravideo SV-328 model and demonstrated its versatile features. He believed that Spectravideo was ideal for creating the MSX standard. Matsushita was particularly impressed and considered Spectravideo to be the ideal basis for the MSX home computer standard project. Nishi also convinced most other Japanese electronics manufacturers to adopt the MSX standard. Soon, Casio, Canon, Fujitsu, Hitachi, Victor, Kyocera, Mitsubishi, Nec, Yamaha, General, Pioneer, Sanyo, Sharp, Sony, and Toshiba joined the project. Nishi also got Korean companies GoldStar, Samsung, and Daewoo on board. Between October 1983 and the summer of 1984, approximately 265,000 devices were sold in Japan by 12 different manufacturers. It was not as big a success as expected at first, which was expected to be achieved through standardization. The standard set by Nishi required complete compatibility between MSX computers, but it did not prevent manufacturers from adding additional features as long as they did not affect compatibility. Pioneer manufactured MSX computers with laserdiscs, while JVC focused on models with video editing features. Yamaha’s devices were designed for music.

In 1983, despite their friendship, Bill Gates was becoming increasingly irritated by Nish’s search for new technologies instead of marketing Microsoft software in Japan. The MSX project took up a lot of Nishi’s time and energy, and although Microsoft in the US officially supported the project, its investment in MSX support was limited. As the Japanese market grew, Gates became increasingly impatient with Nishi. Nishi spent $1 million on an MSX standard advertising stunt featuring a giant dinosaur puppet at Tokyo’s Shinjuku train station. Gates was furious, even though Nishi’s company paid for this unusual marketing event. Gates was preparing Microsoft for its IPO, but he still tried to reorganize things. Gates offered Nishi a plan to merge ASCII with Microsoft and participate in Microsoft’s stock offering. Nishi refused and wanted to remain independent. After painful discussions, they decided to end their collaboration, leaving both men bitter. Nishi claimed that he would have the freedom to start projects that he could not have done with Microsoft, such as designing video and audio chips.

MSX computers were popular in Korea, Japan, South America (Brazil, Chile), the Netherlands, France, Spain, Finland, and the former Soviet Union. Although MSX did not succeed in becoming a global computer standard, MSX devices were versatile and easy to use computers for their time. Thanks to its clear operating system and good Basic interpreter, it proved useful for educational purposes. The Soviet Union made large purchases of MSX1 and MSX2 computers, which were connected to the computer network of the time. An entire generation of Russian programmers grew up using MSX devices. The first MSX computers were imported to Europe in the fall of 1984 by Sony, Toshiba, Canon, Sanyo, Yashica, and Philips. For some reason, the supply of machines in Europe was limited, with only about 100,000 MSX devices available in Europe before April 1985. This limited the total sales figures. The reception varied greatly in different European countries. MSX computers sold well in Italy, but not in the UK, where the ZX Spectrum was already very popular. Everything was tried, including Spectravideo spending millions of dollars on advertising, including a publicity stunt with actor Roger Moore (James Bond).

However, the spread of MSX in the United States was very slow, and Microsoft did not actively promote it. The 8-bit market was dominated by Commodore, which had eliminated most of its competitors by lowering prices. In the United States, MSX devices ultimately remained marginal and unknown. The only MSX machines ever sold widely in the United States were Spectravideo and Yamaha. The easiest place to buy an MSX device in the US was a music store, as Yamaha was supposed to be suitable for making music, but it was claimed that Yamaha’s MSX machines were too difficult to use for this purpose. Yamaha released several MSX machines throughout the 1980s. The MSX1 standard had a lifespan of five years and ended in 1988, as the MSX2 standard had already replaced it two years earlier. By this time, the MSX2+ standard had also entered the market, followed by MSX-Turbo in the early 1990s. More than ten years later, 1chipMSX was designed. The name refers to the fact that all MSX logic is programmed into a single FPGA chip. With its reprogrammable logic, is the 1chipMSX a real MSX device or an emulator, since the chip can also be used to emulate other computers?

The main processor of MSX devices was the Z80A with a clock speed of 3.58 MHz. The video chip was either the TMS9918 or TMS9928 VDP chip, which was also used in Texas Instruments TI-99/4, Colecovision, and Coleco Adam computers. In later MSX models, the chip was upgraded to V9938 (MSX2) and V9958 (MSX2+ and TurboR). The AY-3-8910 is responsible for sound production in MSX devices. It is the same chip used in the Sinclair Spectrum 128. The AY-3-8910 provides a three-channel sound circuit and noise. Thanks to their architecture, MSX computers are well suited for games, and many good games were either written or ported to MSX devices. Many MSX games, especially those released in Europe, were poor translations of popular Sinclair Spectrum games. The Japanese company Konami was well known for its MSX games. For example, many of the most famous games for the 8-bit Nintendo were also released for the MSX. This was not unusual at the time, as Konami, for example, released games for both platforms. In fact, the Metal Gear series originated on the MSX.