A Quiet Classic:

The Canon V-20 and the Beauty of Simplicity

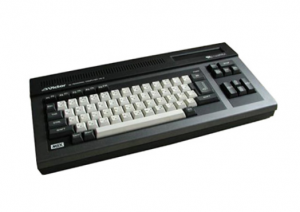

In the early 1980s, Japan’s electronics industry was experiencing a period of explosive creativity. The home computer boom that had begun in Britain and America was spreading across Asia, and Japanese manufacturers — Sony, Panasonic, Yamaha, Toshiba, and Canon among them — saw an opportunity to standardize and globalize the personal computer. The result of this effort was the MSX standard, announced in 1983: a shared architecture intended to unify the fragmented 8-bit computer market under one banner. Within this ecosystem, the Canon V-20, launched in 1984, represented Canon’s entry into the race — a machine that reflected both the ambitions and the limitations of the MSX dream.

Canon was already a respected name in technology, best known for its cameras and office equipment. In joining the MSX initiative, the company sought to extend that reputation into the rapidly growing world of personal computing. The Canon V-20 was built to conform precisely to the MSX specification, which made it compatible with any MSX software or peripheral, regardless of manufacturer. This was the genius of the standard: an MSX program written for a Sony or Yamaha computer would also run on Canon’s, giving users a broad and stable software ecosystem. For a brief moment, it seemed like the future of home computing.

The Canon V-20 was a sleek, compact machine typical of Japanese design aesthetics at the time. Inside, it ran on a Zilog Z80A processor at 3.58 MHz and included 64 KB of RAM — enough to run most MSX programs and games. It featured a Texas Instruments TMS9918A video display processor capable of 16 colours and hardware sprites, and sound came from the General Instrument AY-3-8910 chip, offering three channels of tone and one of noise. In practice, this meant colourful graphics and pleasant, if simple, music — roughly on par with the popular home computers of the time such as the Commodore 64 and the Amstrad CPC.

The machine used Microsoft Extended BASIC, a version of BASIC specifically designed for the MSX standard. For hobbyists and young programmers, this language made the Canon V-20 a gateway into coding: with just a few lines, one could draw shapes, animate sprites, or compose sound effects. The computer booted directly into the BASIC environment, inviting users to experiment and learn — a hallmark of the home-computing era. The V-20 was also compatible with cartridge-based games, which made it appealing to children and families who wanted both play and productivity in a single machine.

Design-wise, the V-20 was elegant. Its keyboard was full-sized and responsive, its layout clear and professional. Canon offered the machine in a tasteful silver-grey case with a minimalistic aesthetic, consistent with the brand’s style in its cameras and calculators. It was also relatively affordable, selling for around ¥49,800 in Japan — a price that placed it within reach of home users while maintaining an air of quality.

Despite these strengths, the Canon V-20 was not a revolutionary computer. It was, like most MSX machines, a carefully built expression of a shared standard rather than a unique creation. In this sense, its individuality was limited: Canon’s implementation differed little from that of Sony, Toshiba, or Sanyo. Its real distinction came from the Canon name — a symbol of reliability — rather than from technical innovation.

When it reached Europe, the V-20 was marketed as a stylish and dependable alternative to other MSX systems. In the Netherlands and Spain, where the MSX format gained some popularity, Canon’s model was well received by enthusiasts. Reviewers appreciated its solid keyboard and attractive design, though they noted that its feature set was nearly identical to that of its competitors. For software, users could choose from a growing library of MSX titles, including games such as Knightmare, Penguin Adventure, and Metal Gear, as well as educational and productivity software.

However, by 1985, the international computer market had shifted dramatically. In North America and Western Europe, the MSX format struggled to gain traction against established brands like Commodore and Sinclair. Canon, despite its prestige, lacked the kind of distribution network and marketing power that might have made the V-20 a household name outside Japan. Meanwhile, in Japan itself, the MSX standard was already evolving toward more powerful second-generation models, such as the MSX2, which offered improved graphics and memory. The V-20 quickly became outdated, and Canon soon withdrew from the computer market entirely to refocus on its core imaging business.

Yet the Canon V-20 remains a fascinating artifact of its time. It embodies a rare moment when dozens of competing manufacturers worked together toward a shared technological goal — something almost unimaginable in today’s proprietary world. It also represents Canon’s brief but earnest attempt to become a player in personal computing. For those who owned one, the V-20 offered a balanced combination of functionality and refinement: a machine that could serve as both a child’s first computer and a parent’s typing tool.

In retrospect, the Canon V-20’s significance lies not in its sales figures, which were modest, but in its participation in the MSX experiment itself. That experiment succeeded in Japan, South America, and parts of Europe, even if it failed to conquer the United States. The V-20 thus stands as a symbol of a global idea — the idea that computers could share a common language across brands and borders.

Today, the Canon V-20 is cherished by collectors for its design, reliability, and place in MSX history. When powered on, its blue MSX BASIC screen still appears with that familiar prompt:

MSX

BASIC version 1.0

Copyright

1983 by Microsoft.

For a brief moment, one can imagine the optimism of 1984 — a time when Canon, Sony, and Yamaha believed that the future of personal computing could be standardized, simple, and beautiful.